PAIKNAMJUNE'D 3

Paik’s Avatar as a virtual post-racial self

Here it is bitches, the core of my research laid bare for judgement before the council. This is also the second-to-last chapter completed from my unfinished manuscript, after this we’re moving into the contemporary with the last written chapter on Inhwa Yeom’s ‘Imposter Kitchen’. As per usual peep da footnotes and memes, and citations are linked throughout this series, but since substack sucks with footnotes you’re just gonna have to do the work yourself lol.

In Global Groove, Charlotte Moorman plays Paik as a cello at around 21 minutes into the broadcast in a performance similar to Moorman and Paik’s performance of Cage’s 26 '1.1499 for a String Player. Paik’s body becomes an interactive object; his status as a raced and sexed individual is both considered and ignored through his objectification as a cello holding strings across his back. Charlotte Moorman becomes Paik’s avatar, and he becomes disembodied, confronting Paik’s status as a subaltern in the West.1 Paik’s choice to utilize Moorman as a performer, especially within the context of her nude or more sexual performative collaborations2, references the historical legacy of utilizing white female bodies by male artists as tools and mediums for expression.3 Rather than use Moorman’s body merely as a tool, as Yves Klein had done, Moorman is Paik’s avatar; she performs as Paik on stage through her raced and sexed body, one differently raced and sexed than Paik's.4 This collaboration between the two allowed Paik to dispense with racialized otherness; he was a white woman on stage, and his work was more in dialogue with European Modernism, which would have appealed to his Western audience.5

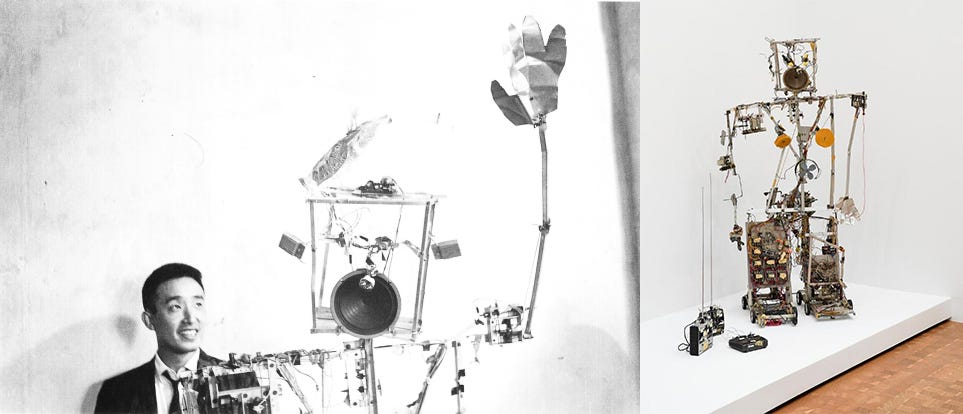

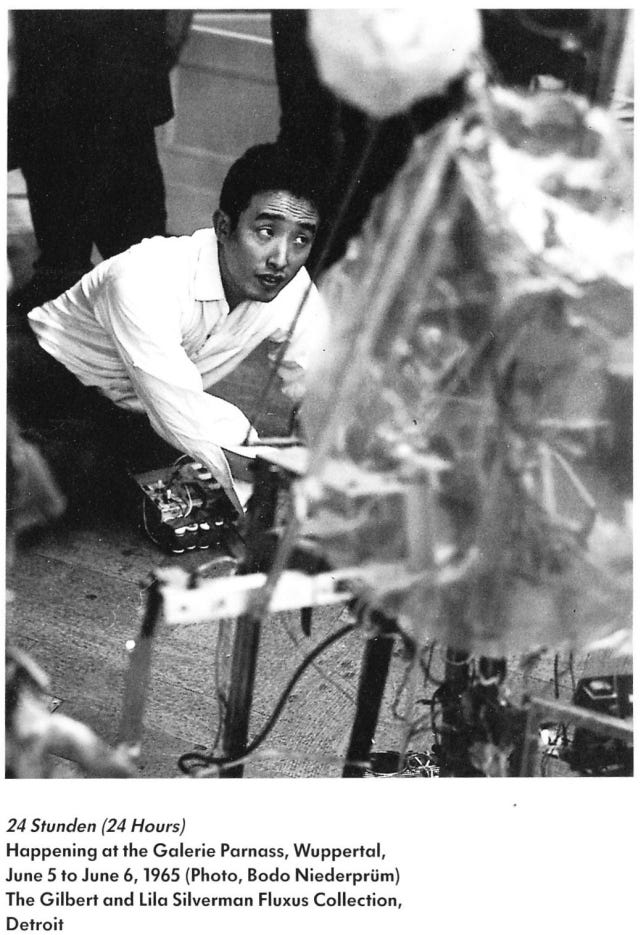

Utilizing Moorman problematized ideas around race, sex, and sexuality, but not more so than Paik’s post-racial, ambiguously gendered, and bisexual robot avatar K-456, who was additionally featured in performances with Moorman.6 K-456 was a controllable robot constructed in collaboration with Shuya Abe for the work Robot Opera in 1964 and subsequent performances, where the robot functioned on behalf of Paik.7 The robot had a loudspeaker for a head, which was able to play audio recordings, breasts and a penis, could move around the stage with the help of a remote, and excrete beans during its performances referencing earlier performance work by Paik.8 As an avatar performing on Paik’s behalf, the robotic body lacks racialized and specific sexed features, and as such, K-456 becomes a post-racial, post-gender being who is sexually fluid.9

However, K-456 wasn’t just a replacement for Paik’s raced and sexed body; Paik was part of the machine. As also demonstrated by TV Buddha, the humanistic element, in terms of how the viewer and the artist, the humans, interacted with the pieces, was an essential component that contributed to the understanding of how “feedback” functioned in the works.10 In TV Buddha, the viewer’s gaze functioned as a similar feedback mechanism to the camera and television recording and broadcasting Buddha’s image; for K-456, the robot was not autonomous and could not function or perform unless it was being controlled by Paik.11 Paik's interest in cybernetics was encompassed in his ideas regarding the relationship between “machines” and “the machinic”; the idea that the machine was fundamentally interconnected to its signals and that it becomes ever-evolving situationally, much like a metaphor for biological organisms and connections.12 Paik did not consider machines as separate and specific entities; he understood them as “open circuits,” more specifically, “we are in open circuits,” and part of a larger network of systems, up to and including the ecological.13 This notion of cybernetics connected Paik to K-456 electronically and biologically, and that both he and the robot were linked into a larger circuitry of social, interpersonal and historical contexts by being mediated by similar factors, namely the increasing ubiquitousness of technology as part of the human experience, and both being subject to “the real,” in that both humans and technology do not exist as impressions of the art, but in their own right.14

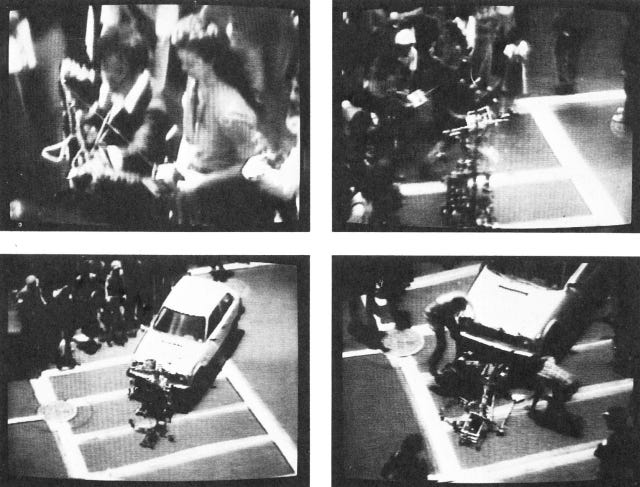

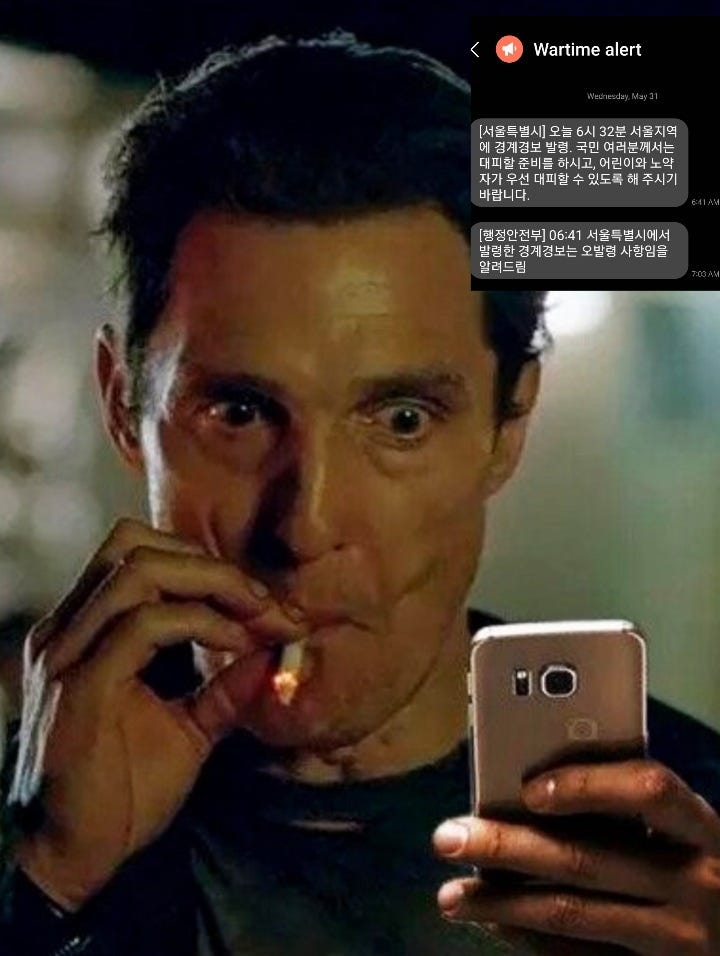

It would be easy to depoliticize K-456 as a utopian ideal of the post-human condition, a being without race and sex and therefore situated in the equitable and non-heirarchal, due to Paik’s views of cybernetics, in which he seemed to be exploring how robots and machines can function in ways that can expand the definition of being human.15 However, the positionality Paik has explored up until this point, Asian, other, subaltern, Orientalized subject, would be refused. K-456 could act on Paik’s behalf in ways that Paik himself was unable to as a Korean War refugee and as occupying a raced body in the West.16 K-456’s attempt to cross the Brandenburg Gate in 1965 is a significant incident, and preceded Robot Opera, yet is little discussed in comparison to K-456’s performance of being hit by a car in Manhattan.17 Being directly impacted by the Korean War, and having fled Korea in response, Paik’s performance in Berlin was an attempt to cross the divide between countries divided along lines of ideology and the wars they justified.18 Paik remotely controlled the robot and steered it towards the Brandenburg Gate in what was labelled as “almost an international incident” as described by The New York World-Telegram and Sun.19 This was a deliberate attempt by Paik to cross geographic divides impacted by Western imperialism’s actions from the Cold War, and also to situate himself and K-456 in relation to being truly unable to cross those divides.20 This performance highlighted the ways in which K-456 acted on Paik’s behalf as his avatar, but as the intentions and physical actions are controlled by Paik, K-456 extends Paik’s physical body into the realm of the cyborg as a physical entity taking up real space but reaching into in ways Paik can’t; his prosthesis.

Both K-456 as an avatar and extension of Paik’s identity embrace the model of the cyborg that questions and problematizes “models of identity that do not adhere to static nation-state, gender, race, or class”.21 The cyborg is fluid, subject to change between different distinctions of gender, sexuality, nationality, and race, while simultaneously existing outside of the context of those same set of paradigms.22 Examining K-456 through the lens of the cyborg, and considering the robot a prosthetic of Paik, their performances together render Paik as post-race and post-gender, as Paik takes on the robot’s attributes by becoming connected to it. It’s worth consideration to reflect that Paik’s avatar went from a post-gender being to being specifically gendered as female in discourse, although Paik’s previous use of female bodies in his work, including those of Alison Knowles and Charlotte Moorman shouldn’t render this surprising, the robot remains a post-gender being by being sexed as female through a male-sexed collaborator.23

In “A Cyborg Manifesto” Donna Haraway states:

“[…] the cyborg has no origin story in the Western sense; a “final” irony since the cyborg is also the awful apocalyptic telos of the “West’s” escalating dominations of abstract individuation, an ultimate self untied at last from all dependency, a man in space”24

Haraway is considering issues related to the cyborg in the context of a post-gender being in subaltern terms, but her acknowledgement of subaltern status as stemming from Western, white imperialism and colonialism is explicitly stated by her consideration and characterizations of cyborgs as oppressed women of color.25 While her argument becomes relevant to the post-racial, her idea of the cyborg as based outside a Western center questions Haraway’s role in perpetuating techno-orientalist ideas and embracing discourse where only the subaltern is subject to the post-gender and post-racial.26 K-456 did in fact, not come from the West, nor was it a Western creation; a Korean artist collaborated with a Japanese artist to create a machine, a machine that was subject to the actions of the machinic, but took on the role of Paik in order to perform and present as ways that Paik couldn’t.27 However, one could argue that by merely engaging in the practice of utilizing technology, including performative work featuring K-456, Paik continued to play into the same Techno-Orientalist narratives that were invoked by works such as TV Buddha rather than addressing the post-racial condition.28

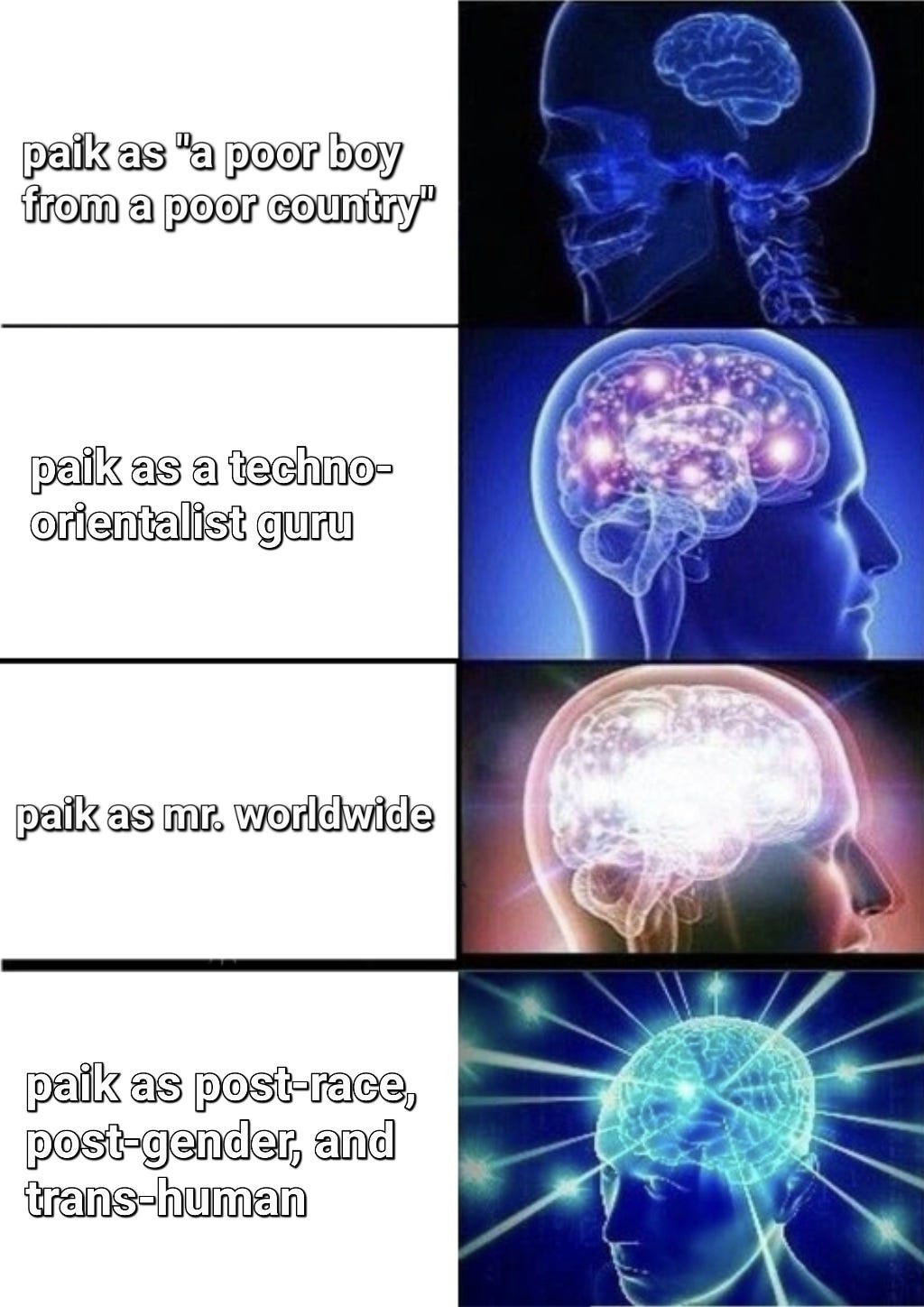

Paik, as himself, could only be defined amongst his European peers as “other” based on visual characteristics as someone raced as Asian. K-456 was able to escape such definitions by being racially illegible, ie, lacking any raced characteristics, and existing as an exotic being by nature of its materiality while also being a blank slate for others, including Paik, to project actions onto. K-456 may be othered to the degree that it’s a robot lacking free will and any true sense of an organically or societally derived identity; it escapes presuppositions of identity “raced” others are subject to.29 Paik was not a passive recipient of a racist gaze; he utilized the framework and historicity of racism against Asians by performing as the both techno-orientalist fantasy of a technological and spiritual guru, and as not performing, and allowing K-456 to act on his own behalf while maintaining a particular understanding of his positionality in the West. The effectiveness of K-456’s universality as an avatar for both Paik and a potential post-humanism was because of techno-utopian ideals present in technoculture that proposed a post-racial and post-gender future, which offered a philosophical and cultural alternative to technology as a method of absolute control and violence that was associated with the Cold War.30

K-456 and Paik’s assemblage robot works don’t give viewers the satisfaction of visual legibility of gender or cultural markers that are easier to identify with humans’ raced and sexed bodies, making them harder to contextualize within racial and socio-political frameworks. Legacy Russell, quoting James C Scott, states, “Legibility [becomes] a condition of manipulation”.31 Race, as an “embodied discourse” that isolates “othered” narratives as non-participatory by nature of their visual legibility as opposed to a White and Western center demarcated as default, becomes disembodied in Paik’s works.32 As a “tool for happenings” a piece meant to perform both its functions and dysfunctions in the same manner that Paik approached his performance works, K-456’s appearance de-raced and de-sexed that of Paik by being an open and naked structure with its functionality visibly legible through its bare circuitry.33 By performing in similar ways, the robot was both his self-portrait and his avatar, and yet could also address universal anxieties concerning industrialization, automatism in late capitalism, and the loss of self through technology and increasing mechanization.34

This principle expanded the mythologizing of Paik beyond simply an object of Orientalism and Techno-Orientalism, to create a universal figure, a symbol of the artist. This allowed K-456 to be understood within a Western canon, and as the robot de-raced Paik as a Korean or Asian artist, the robot’s context in a Western avant-garde erased its own identity and connection to Paik.35

Paik’s utilization of “race as technology”, by creating a post-racial self, calls into question some of his ways of “doing race” in his later robot works. In Self Portrait(Eskimo Man) (1995) we see a robot mostly made up of am/fm radios, with a fan for a body, a battery eliminator as a face, holding a broken umbrella, and only two small screens; one on the robot’s head and one as its right foot. While his use of radios in the work could be a reference to his background in music or his work in satellite broadcasts, this robot is constructed of fewer screens than most of his other robot works.36 It’s notable that the work isn’t only Paik’s perception of a person raced as First Nations, but also himself, as the main text of the title addresses that the work is a self-portrait. Through the avatar of this sculptural robot work, Paik roleplays as someone else, raced as “other,” albeit not Asian, but subaltern nonetheless. While his other robot sculptures sometimes have raced indications as props or Asian scripts, Self Portrait(Eskimo Man) does not, making this sculpture also illegible in terms of raced associations outside of the title. Rather than specifically engaging in Orientalism, perhaps Paik is playing into a racial imaginary that characterizes the “other” as more primitive, much like his inclusions of the Navajo and Nigerian performers in Global Groove. This would then play into his public characterizations of self as racially Asian and as hailing from a “backward country,” creating a dialectic in terms of his associations with other raced bodies. This post-racial portrait, rather than de-racing, differently races Paik, making his existence and experience as “other” indistinguishable, and parallel to the raced experiences of other marginalized people of color.

As a raced artist that was a member of a Western avant-garde, Paik was simultaneously limited by being othered and expected to work from an Asian positionality, while also free in the same measure to construct a public self that was unbounded by geographic limitations and expanded on his personal cartographies related to place and identity. His utilization of race-based identifiers, as in the examples of I-ching and Zen Buddhism in some works, and his refusal of race-based identifiers in others, such as K-456, map Paik’s complicated self-representation that addresses the framework through which his work was received, namely Orientalist constructions. By acknowledging his works’ relationship to technology and Western associations of what a technologized Asia means for the West, Paik was able to expand his work under the guise of engaging with Techno-Orientalism. By the nature of working with new media and performance, he was able to move past his position as an Orientalized subject by utilizing the bodies of women and of robots to perform race, gender, and the role of the male artist. He effectively played into Western ideas of the East and took advantage of his fetishized racial positionality to question and problematize issues of racial identity within the West. Paik’s process brings to light the inherently problematic nature of trying to construct a global canon of art from a Western perspective, and how Asian, and specifically Korean artists, respond due to Korea’s positionality in geopolitics as a post-colonial state.37

😩 I’m gonna be so fucking forreal with you fam. This took a while. Life has been pretty fucking insane. Between facilitating a performance art project for my collaborator extraordinnaire Jun!yi Min, Seoul stuff (which I’ve barely been present for), another group show in October (so far lol), and a thousand other things behind the scenes, I’ve been dealing with severe burnout. I finally totally crashed after the performance on June 14th and have been sorta stuck in a really really dark existential depression, only worsened by what’s happening geopolitically; in total lizard brain mode from a PTSD symptom relapse. Doing my best to claw my way back out, but in the immediate interim, this substack will follow irregular posting (as if we haven’t already gotten to that point lol) as I take some time and space to figure some shit out. love you twin. xoxo.

Rhee, “Asian Bodies,” Pg 70.

NO BUT LITERALLY. Shirtless to full-frontal nudity.

Ibid., Pg 67.

Ibid.

Ibid., Pg 62.

Landres, Sophie. "The First Non-Human Action Artist: Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik in Robot Opera." PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 40, no. 1 (2018): Pg 13. Really interesting paper that brings up the relationship of labor on behalf of “the artist”, the artist being the robot k-456

Landres, “Non-Human Action Artist,” Pg 13.

Rhee, “Asian Bodies,” Pg 62.

Ibid.

Yoo, “To be Two Places,” Pg 33.

Ballard, Susan. "Nam June Paik, Cybernetics and Machines at Play." Conference Paper at Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Electronic Art, ISEA2013, Sydney, January 1, 2013.

Ibid.

Landres, “Non-Human Action Artist,” Pg 15.

Ballard, “Nam June Paik,” Pg 1.

Ibid.

Manifestos, Pg 24.

Ballard, “Nam June Paik,” Pg 1.

Soraya Murray, “Cybernated Aesthetics: Lee Bul and the Body Transfigured,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 30, no. 2 (2008): Pg 40. This piece concerns the work of another trans-humanist artist, Lee Bul, but the writer makes a direct reference to Paik in order to develop a working definition for “cybernetics”. Also Lee Bul is fucking amazing, check out her work.

Ballard, “Nam June Paik,” Pg 2.

Yoo, “To be Two Places,” Pg 35.

Ibid.

Ibid. This is a really important and little discussed point; the physical wall between East and West Berlin as a proxy for the DMZ separating North and South Korea; both places serving as ideological battlegrounds. Paik’s invocation of “crossing the border” could be interpreted as an invocation of home and homeland, and what it means to physically bridge the barrier between two places ideologically split by Western politik. God forbid Westerners acknowledge Paik was Korean and was maybe making work from that positionality?? This is the main point worth repeating a thousand times

Author unidentified, New York World-Telegram and Sun, March 14, 1966, Nam June Paik Archive, box 63, folder 1, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Yoo, “To be Two Places,” Pg 36.

Murray, “Cybernated Aesthetics,” Pg 39.

Ibid.

Donna J. Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991), 149-181. Pg 97. We gonna get into this text repeatedly. Also disclaimer: there is criticism towards Haraway (by Yoo, Rhee, etc) for this text for her use of “oriental” to describe Asian, which is decidedly unfeminist in contemporary readings, but I also don’t want to cut her slack for “product of her time” blah blah because in that line she actively feeds into Anti-Chinese Techno-Orientalist narratives and kind of embraces them as a universal standard of understanding. Like you’re doing so much girl!!!! Why did you fumble this 😭 ugh

Rhee, “Asian Bodies,” Pg 62-66.

Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto,” Pg 67.

Ibid., Pg 68-71.

Ibid. Pg 71. ACTUAL TEA ON HARAWAY’S USE OF ‘ORIENTAL’ IN CONTEXT: Haraway specifically states ”Oriental,” in quotations, while referring to Asian women in her text, and while this could be considered a critical viewpoint, as the term does exist in quotations, she is referring to “their nimble little fingers” playing into problematic narratives around Asian women’s domesticity and characteristics. Like girl, what the hell.

Barrett, “Nam June Paik,” Pg 2.

Yoo, “To be Two Places,” Pg 34.

Ibid., Pg 36-38.

Roh, et al., “Techno-Orientalism,” Pg 215.

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun; Introduction: Race and/as Technology; or, How to Do Things to Race. Camera Obscura 1 May 2009; 24 (1 (70)). Pg 24. Literally such a good paper addressing ontological questions around “race”-building and its developmental history as social technology. HIGHLY RECOMMEND.

Ibid.

Broeckmann, Andreas, "The Machine as Artist as Myth" Arts 8, no. 1 (2019): Pg 4.

Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto,” Pg 72.

Russell Legacy. 2020. Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. London: Verso. Pg 16.

Chun, “Race and/as Technology,” Pg 24.

Landres, “Non-Human Action Artist,” Pg 18.

Yoo, “To be Two Places,” pg 34.

Landres, “Non-human Action Artist,” Pg 18.

Douglas, Barrett G.. "TECHNOLOGICAL CATASTROPHE AND THE ROBOTS OF NAM JUNE PAIK." Cultural Critique, no. 118 (2023): Pg 56.

Rhee, “Asian Bodies,” Pg 63.

Gregory Zinman; Nam June Paik's Etude 1 and the Indeterminate Origins of Digital Media Art. October 2018; (164): Pg 8.

Foster Hal. 2011. Art Since 1900 : Modernism Antimodernism Postmodernism. 2nd ed. London: Thames & Hudson. Pg 51,